- Home

- Philip Collins

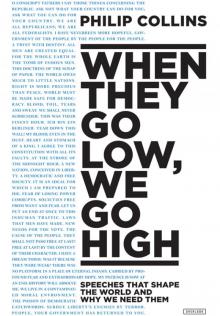

When They Go Low, We Go High

When They Go Low, We Go High Read online

when First Lady Michelle Obama approached the podium at the 2016 Democratic National Convention, nobody could have predicted that her rousing and emotional “When they go low, we go high” speech would go on to become the motto for the political left and an anthem for opponents of oppression worldwide. It was a speech with the kind of emotional pull rarely heard these days, joining a long list of addresses that have made history. But what about Obama’s speech made it so great?

When They Go Low, We Go High explores the most notable speeches in history, analyzing the rhetorical tricks to uncover how the right speech at the right time can profoundly shape the world. Traveling across continents and centuries, political speechwriter Philip Collins reveals what Thomas Jefferson owes to Cicero and Pericles, who really gave the Gettysburg Address, and what Elizabeth I shares with Winston Churchill.

In telling the story of great and sometimes infamous speeches—including those from Lincoln, Woodrow Wilson, JFK, Martin Luther King, Jr., Disraeli, Hitler, Elie Wiesel, Margaret Thatcher, and Barack and Michelle Obama—Collins breathes new life into words you thought you knew well, telling the story of democracy. Whether it’s the inaugural addresses of presidents or the revolutionary writings of Castro, Pankhurst, and Mandela, Collins illuminates and contextualizes these moments with sensitivity and humor.

When They Go Low, We Go High is a strong defense of the power of public speaking to propagate and protect democracy and an urgent reminder that when great men and women speak to us, their words can change the world.

To the memory of Jennifer Anne Taylor (1942–2014)

and Frederick John Collins (1940–2015)

Copyright

This edition first published in the United States in 2018

by The Overlook Press, Peter Mayer Publishers, Inc.

141 Wooster Street

New York, NY 10012

www.overlookpress.com

For bulk and special orders, please contact [email protected],

or write us at the above address.

© 2018 Philip Collins

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast.

ISBN: 978-1-4683-1617-9

CONTENTS

Dedication

Copyright

Acknowledgements

List of Speeches

PROLOGUE

The Perils of Indifference

CHAPTER 1

Democracy: Through Politics the People Are Heard

CHAPTER 2

War: Through Politics Peace Will Prevail

CHAPTER 3

Nation: Through Politics the Nation Is Defined

CHAPTER 4

Progress: Through Politics the Condition of the People Is Improved

CHAPTER 5

Revolution: Through Politics the Worst Is Avoided

EPILOGUE

When They Go Low, We Go High

Bibliography

Index

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I have been privileged to write speeches in one great institution and about them in another. In 10 Downing Street I had the pleasure of writing for Tony Blair, which changed the course of my career, if such a word is appropriate for my random array of jobs. The Times then took me in and my thanks are due to Daniel Finkelstein for suggesting that move in the first place. Then also to successive editors, James Harding and John Witherow, for commissioning the speech analysis format which I have followed in this book.

For the way the format stretched into an ambitious thesis, I salute Claire Conrad, my agent, and Helen Garnons-Williams, my editor, whose diplomatic skill in making a major rewrite sound like a tweak was exemplary. I think I minded more, not less, because she was always right. Thanks to Siobhan Reynolds for reading things so that I didn’t have to and to the team at 4th Estate for doing such a professional job, so quickly. I hope I did the same.

Finally, an enormous yes to Geeta Guru-murthy and the two perfect perishers, my chief critics, Hari and Mani Collins. If any errors have eluded their searching questions the fault for that will be mine. That’s their story, anyway. My story is in the pages that follow.

SPEECHES

Marcus Tullius Cicero: First Philippic against Mark Antony, The Senate, the Temple of Concord, Rome, 2 September 44 BC

Thomas Jefferson: Equal and Exact Justice to All Men, First Inaugural Address, Washington DC, 4 March 1801

Abraham Lincoln: Government of the People, by the People, for the People, The Gettysburg Address, 19 November 1863

John F. Kennedy: Ask Not What Your Country Can Do for You, Washington DC, 20 January 1961

Barack Obama: I Have Never Been More Hopeful about America, Grant Park, Chicago, 7 November 2012

Pericles: Funeral Oration, Athens, Winter, c. 431 BC

David Lloyd George: The Great Pinnacle of Sacrifice, Queen’s Hall, London, 19 September 1914

Woodrow Wilson: Making the World Safe for Democracy, Joint Session of the Two Houses of Congress, 2 April 1917

Winston Churchill: Their Finest Hour, House of Commons, 18 June 1940

Ronald Reagan: Tear Down This Wall, The Brandenburg Gate, Berlin, 12 June 1987

Elizabeth I of England: I Have the Heart and Stomach of a King, Tilbury, 9 August 1588

Benjamin Franklin: I Agree to This Constitution with All Its Faults, The Constitutional Convention, Philadelphia, 17 September 1787

Jawaharlal Nehru: A Tryst with Destiny, Constituent Assembly, Parliament House, New Delhi, 14 August 1947

Nelson Mandela: An Ideal for Which I Am Prepared to Die, Supreme Court of South Africa, Pretoria, 20 April 1964

Aung San Suu Kyi: Freedom from Fear, European Parliament, Strasbourg, 10 July 1991

William Wilberforce: Let Us Make Reparations to Africa, House of Commons, London, 12 May 1789

Emmeline Pankhurst: The Laws That Men Have Made, The Portman Rooms, 24 March 1908

Isidora Dolores Ibárruri Gómez (La Pasionaria): No Pasarán, Mestal Stadium, Valencia, 23 August 1936

Martin Luther King: I Have a Dream, The March on Washington, 28 August 1963

Neil Kinnock: Why Am I the First Kinnock in a Thousand Generations?, Welsh Labour Party conference, Llandudno, 15 May 1987

Maximilien Robespierre: The Political Philosophy of Terror, The National Convention, Paris, 5 February 1794

Adolf Hitler: My Patience Is Now at an End, Berlin Sportpalast, 26 September 1938

Fidel Castro: History Will Absolve Me, Santiago, Cuba, 16 October 1953

Václav Havel: A Contaminated Moral Environment, Prague, Czechoslovakia, 1 January 1990

Elie Wiesel: The Perils of Indifference, The White House, Washington DC, 12 April 1999

PROLOGUE

THE PERILS OF INDIFFERENCE

The Birth of Rhetoric

The beautiful ideas of rhetoric and democracy were born in the same moment, in the winter of 431 BC in Athens, when the statesman Pericles stood to deliver his Funeral Oration. It might seem grimly appropriate, as democracy struggles through yet another of its crises, that its birth should have been marked by a funeral oration. There are plenty of predictions that another doleful eulogy will be required soon. Democracy is going through a troubled time and rhetoric is in the dock beside it. The chapters that follow have been written in the conviction that no funeral oration is needed for either.

In his speech, Pericles commemorat

ed the sons of Athens lost in the Peloponnesian War, but he also applauded the glory of the city and made a sparkling case for government with the consent of the people. The currency of persuasion in a democracy, he argued, is not force or authority. It is speech. The moment that fiat is replaced by consent is the moment that oratory begins to count. Rhetoric and democracy are twinned; their histories run together. In this book I shall tell these parallel stories and mount a vigorous defence of the practice of politics in a time when cynicism has become the norm.

The politics of ancient Athens and Rome are distant and unfamiliar to us today except for a single unchanged element. The spectacle of a single person walking to a podium to persuade an audience remains now exactly as it was then. Very few disciplines survive twenty centuries. Nothing of the science of the period is of much more than curiosity value. The drama is still performed, but most of its stylistic conventions are anachronisms. Disciplines tend to date, positions are superseded, ideas fall into disuse, new frontiers are discovered. None of that is true of rhetoric. Reputations in the ancient republics were won and burnished by theatrical performance, and in politics today, they still are. Whether they know it or not, public speakers of all the succeeding ages owe a debt to Aristotle’s The Art of Rhetoric and Cicero’s De oratore.

Cicero gives us a portrait of the ideal orator. There was no separation, for him, between rhetoric and politics, so the orator needed to be steeped in political wisdom, to display a command of language and psychological insight into the audience, to be witty, shrewd and funny. In an age in which speeches were delivered by heart, the orator needed perfect recall. They also needed a resonant voice, although not all of them have had it. Demosthenes practised with pebbles in his mouth with the aim of improving his timbre. Abraham Lincoln was barely audible at Gettysburg, Winston Churchill sought medical help over his lisp, and John F. Kennedy’s voice was often said to be too reedy for his grand words.

The central point of De oratore, what Cicero calls the Topic, should be engraved over the desk of every speechwriter: make sure you know your central point. This is advice that has worked for all speakers, in every nation and every time, and will always work. The central point of this book is that liberal democracies are the best imaginable places to live and that this claim needs to be compressed poetically into a clear message of hope. As I write, democracy is once again coming under threat from populists, and rhetoric is, like nostalgia, one of those things that are always said not to be as good as they used to be. The threat to democracy is linked to the attack on rhetoric. If we want to attend to the good health of our democracy, and we really must, then we need to attend to the integrity of the way we speak about politics.

The Sophisticated Speechwriter

For many years it was my job to write the words that carry public arguments. As the chief speechwriter to Prime Minister Tony Blair I tried to draft words that did justice to the hopes and passions of politics while at the same time respecting the limitations involved. It was a fascinating and privileged vantage point on the politics of Britain and its chief allies. If Blair’s speeches feature prominently in the chapters that follow it is because of that personal insight rather than necessarily a claim that the words bear comparison with the finest rhetoric in history.

During my time as Blair’s speechwriter I regularly fielded the accusation that rhetoric had declined and that the duplicity of crafted words was contributing to the low repute of politics. These are dangerous illusions that need to be countered. Rhetoric is not crafted deception and it is not worse than it was. There is a serious prospect that, in our time, we are losing faith in politics. The words of politicians float by, practised and polished, but profligate. The respect, veneration and hope first expressed by Pericles, has gone missing. It is the grand purpose of this book to help to call it back.

The accusation that rhetoric is simply duplicity has a long pedigree, and speechwriters have always come in for opprobrium as purveyors of fine falsehoods. In the sixth and fifth centuries BC, Greece was making the transition from aristocracy to democracy. Social class was no longer enough to support a political career, as every free male citizen enjoyed the right to speak in the assembly. This created a novel demand for tuition in the art of rhetoric. A band of itinerant writers and teachers of oratory met that demand, for high fees. They were known as the Sophists and they came in straight away for vilification. Taking money for instruction was thought to be ignoble and the Sophists were immigrants who imported new and unwelcome ideas, such as the notion that truth was not transcendent but emerged from the clash of arguments.

In 423 BC, in The Clouds, Aristophanes was the first to note that rhetorical genius can be turned to ill effect or can conceal dubious motives: It’s just rhetoric, we say. Aristophanes satirises Socrates’ rhetorical fluency and his ability, in the boast of the Sophist Protagoras, to ‘make the weaker case appear the stronger’. In The Clouds Aristophanes has Socrates teach a boy how to argue that a son should beat his parents. They take revenge by burning down Socrates’ ‘Thinking Shop’. Plato, who lived in Athens in the generation following the arrival of the Sophists, shared Aristophanes’ distrust and wrote the classic statement of suspicion about rhetoric. In his dialogue Gorgias, he condemned rhetoric as a ‘knack of flattering with words’ which led not to truth but to mere persuasion. Plato regarded rhetoric as a low art form of no great import, like cookery, in particular pastry cookery. The writer might be an enchanter, thought Plato, but his work touched the surface alone and never penetrated to the deeper truths.

Plato’s villain, the superficial malignant, was the Sophist speech-writer rather than the speaker himself. Tacitus echoed the complaint at the beginning of the second century AD. When the emperor Nero gave a speech praising his predecessor Claudius, Tacitus criticised Nero for reading words written by his tutor, Seneca. It is often said that political leaders would be more authentic if they wrote their own material. Many of them, in fact, have. Cicero was a student and a theorist of oratory as well as a practitioner. Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson and Abraham Lincoln all composed their own words. Franklin D. Roosevelt wrote his famous Inaugural Address of March 1933. Winston Churchill never stopped reading and writing his own speeches. Even now, the most senior politicians write more of their own words than is commonly supposed. Barack Obama was heavily involved in his major speeches. I can attest that Tony Blair often took his fountain pen and scribbled his own words in a spider hand.

But why should a politician not seek help for a task as central to democracy as making a case? George Washington got help for his Farewell Address from Alexander Hamilton and James Madison, though neither took the title of speechwriter. Judson Welliver, the man credited with coining the phrase ‘the Founding Fathers’, was known as a ‘literary clerk’ when he wrote for Warren Harding and Calvin Coolidge between 1921 and 1925. Herbert Hoover always denied that French Strother wrote his words. Franklin D. Roosevelt had a group of advisers that he called his Brains Trust, to help with his speeches.

The first man to be given the title of speechwriter in the White House was Emmet J. Hughes, who wrote for President Dwight D. Eisenhower. The turning point, when the speechwriter becomes a shadowy figure of national importance, is often said to be President Kennedy’s relationship with his amanuensis Ted Sorensen, though it was actually Richard Nixon who was the first president to establish a Writing and Research Department in the White House. The supposed promotion to a department of their own concealed a change that would have puzzled and irritated Cicero. Before they were separated into a distinct craft, writers took part in policy deliberation. In Nixon’s new dispensation they became wordsmiths. The industrial term describes the demotion from profession to trade, from statecraft to prettifying decisions made somewhere else.

The speechwriting office, once established, never closed, and every president employed a host of writers, sometimes as many as six. There is a cultural difference here between the common practice of America and that of Britain

. British speechwriters tend to be cats who prowl alone, like Joe Haines who wrote for Harold Wilson and Ronald Millar who wrote some of Margaret Thatcher’s best speeches. Though the British speechwriter writes solo, he or she has to contend with the attention of a multitude. Part of the job is to be editor-in-chief, fielding the reams of unsolicited passages sent in by academics and pet projects pushed by ministers. It is a curiosity of the job that people seem to believe that if they send in a few lines with no context then the speech can be assembled from all these bits, like flat-pack furniture comprised of the parts from different chairs. In Britain it can be a lonely task, whereas counterparts in the White House are collectively crafting clap lines in pairs or, for big speeches such as the State of the Union, in numbers even greater.

However they do it, their words really count. Robert Schlesinger, the author of White House Ghosts, a history of presidential speech-writers (one of them was his father Arthur, who wrote for Kennedy), has suggested that there may be cause and not just correlation in the fact that the one-term presidents – Ford, Carter, George H. W. Bush – were poor speakers while the charmers – Reagan, Clinton, Obama – talked themselves into second terms. No politician ever fares better with phrases ragged and unformed. Their words would, to use an old speechwriting joke, be read long after Milton and Shakespeare are forgotten – but not until then. For all the fine speakers who make it for the consideration of posterity there are countless would-be orators whose dreary platitudes would have benefited from the attention of a writer with an ear for rhythm.

The Temple of Concord

The enemy of good writing is not the good speechwriter. It is bad politics. When a politician is timid they will avoid all controversial topics. They will then have nothing to say. The cause of the distance that opens up between the people and politics is empty talk. Then, into the vacuum, there is always the danger that something unpleasant can insert itself. That is where we will find ourselves heading again, if we fail to attend to the quality of political speech. The suggestion of manipulation by fiendish speechwriters is the first denigration. The second accusation is that rhetoric is now boring. The travails of democracy are attributed to the poor quality of contemporary speech. The truth is closer to the opposite. If speeches are duller today than they once were, that is largely on account of the manifold successes of the liberal democracies.

When They Go Low, We Go High

When They Go Low, We Go High